Cook Islands Natural Heritage Articles

Golden Plovers and the Tere Party to Alaska

During our southern summer there are dull-brown birds on open grassy areas and along the shore. They alternate between standing motionless and jogging a few metres, periodically pecking at an insect or other food on the ground. Each is alone within a large territory.

During our southern summer there are dull-brown birds on open grassy areas and along the shore. They alternate between standing motionless and jogging a few metres, periodically pecking at an insect or other food on the ground. Each is alone within a large territory.

These birds are the Pacific Golden-Plover (Pluvialis fulva). Traditional names reflect their "tuuu-ree" alarm call: Tōrea (Rarotonga, Mangaia, Aitutaki, Manihiki and Rakahanga), Toretōrea (‘Ātiu, Ma‘uke and Miti‘āro), and Tuli (Penrhyn, Pukapuka and Nassau).

On Rarotonga there are usually two to three hundred plovers, with more than 70% of them on the grassed areas of the International Airport. The remainder are scattered along the shore and on smaller grasses areas, such as large lawns and playing fields. The birds on the airport are relatively secure from cats and dogs and they can sleep in their territories at night. Birds in less secure areas fly to safer roosting areas for the night, such as the airport runway. In Hawaii some have learnt to roost at night on multi-storey buildings.

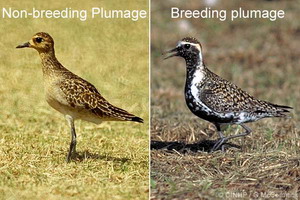

During February and March the plovers change their feathers to become suitably attired for the courtship parties they will hold in Alaska. While in Alaska they have been described as "an aristocrat among birds. Everything about [them] is distinctive." There they have a jet-black breast and belly, a golden yellow and black back, and striking head markings. They also move in a stately and dignified manner.

It is a long way from Rarotonga to Alaska – 9,000km, about three times the distance from Rarotonga to New Zealand. The journey is over the ocean with only a few islands where they might take a rest. Research indicates that most birds undertake the journey non-stop, while some take a few hours or a couple of days to re-fuel along the way. Under good conditions plovers can sustain 80kph and could complete the 9,000 km journey in about five days. Such a journey would require about 50 grams of fat-fuel – a typical bird leaves here at 150 grams to arrive in Alaska at 100 grams with about 10 grams of fuel in reserve.

The Rarotonga Tōrea-section of the tere party leave mainly in the first or second week of April, while those closer to Alaska can delay their departure a week or two. Hawaiian plovers, the Kōlea, leave mainly in the last week of April to undertake their 3000-kilometre journey in about 36 hours. On Rarotonga the Tōrea assemble and depart in groups of two to four dozen at dawn from the International Airport – but not on a jet-plane.

There is little specific data on plover navigation. Experiments on other migratory birds show that they use various stars at night and the sun during the day. There is also evidence that some birds can detect the earth’s magnetic field although its use in navigation remains controversial.

When the plovers arrive in Alaska spring has arrived, the snows are melting, plants are sprouting, and insects are emerging in abundance. On the dry hills above the bush-line, most male plovers return to the same breeding territory they occupied the previous year. In their aristocratic manner they perform dramatic aerial display to attract a new mate. If all goes well each male and his bride will build a nest on the ground of moss and lichen, she will lay four eggs, and they will share the role of incubating the eggs for 26 days when the chicks hatch. Both parents care for the young until they can fly at three weeks of age.

On the Alaskan hills the hatchings start appearing in early July and reach a maximum number two weeks later. With 24-hours of daylight and abundant food they grow rapidly – out of the nest within a few hours, and flying in three weeks. By early August the adults start abandoning their offspring and by early September all adults have left the breeding grounds. They go to areas of abundant food, fatten themselves, and migrate back to the tropics. Most return to the same country and same plot of ground they occupied the previous area.

By mid-September the juveniles are driven southward by falling temperatures and diminishing food supplies. They have all left Alaska by mid-October and hopefully they have found a suitable area in the tropics to live. Although the young probably have an innate sense to migrate southward to the tropics, there is no evidence that they migrate to the area occupied by either of their parents.

First published Cook Islands News April 2003, republished 9 April 2005

About Gerald McCormack

Gerald McCormack has worked for the Cook Islands Government since 1980. In 1990 he became the director and researcher for the Cook Islands Natural Heritage Project - a Trust since 1999.

He is the lead developer of the Biodiversity Database, which is based on information from local and overseas experts, fieldwork and library research. He is an accomplished photographer.

Gerald McCormack has worked for the Cook Islands Government since 1980. In 1990 he became the director and researcher for the Cook Islands Natural Heritage Project - a Trust since 1999.

He is the lead developer of the Biodiversity Database, which is based on information from local and overseas experts, fieldwork and library research. He is an accomplished photographer.

Citation Information

McCormack, Gerald (2005) Golden Plovers and the Tere Party to Alaska. Cook Islands Natural Heritage Trust, Rarotonga. Online at http://cookislands.bishopmuseum.org. ![]()

Please refer to our use policy