Cook Islands Natural Heritage Articles

Frigatebirds - Our Vulnerable Pirates

Frigatebirds are the largest seabirds residing in the Cook Islands, with wingspans of 180-220cm. They are uniformly black above, and black or black with a white breast below; their wings are long, angled, and sharp tipped; their tails are long, and deeply split into two sections. They do not nest on Rarotonga, or on any inhabited Southern Group island, although they often soar over the coast of inhabited islands when there is a storm at sea. As a result they are sometimes called Storm Birds or Hurricane Birds. It is not clear why frigatebirds congregate at islands during storms, but it is probably because they find flying at sea more difficult and if they land on the water they usually die.

Frigatebirds are the largest seabirds residing in the Cook Islands, with wingspans of 180-220cm. They are uniformly black above, and black or black with a white breast below; their wings are long, angled, and sharp tipped; their tails are long, and deeply split into two sections. They do not nest on Rarotonga, or on any inhabited Southern Group island, although they often soar over the coast of inhabited islands when there is a storm at sea. As a result they are sometimes called Storm Birds or Hurricane Birds. It is not clear why frigatebirds congregate at islands during storms, but it is probably because they find flying at sea more difficult and if they land on the water they usually die.

Masters of the air

Frigatebirds have weak muscles, which makes their flapping flight slow and laboured. In contrast they are superbly designed to soar and glide on the wind, being the lightest of all birds per unit of wing area. They can soar and glide continuously for several weeks, often travelling more than 600 kilometres from their colonies. They make use of the Trade Winds and thermal updrafts, often soaring at great heights - sometimes reaching 2,500 metres, a seabird record. They can sleep on the wing, but often approach islands in the evening to roost on trees after dark, especially on calm nights when soaring is difficult. Roosting on trees affords the best protection from predators and the best chance of a favourable wind to launch themselves in the morning. On unpeopled islands without predators they can roost on the ground in open areas where the wind can provide the necessary lift for takeoff. They cannot rest on the sea because without waterproof feathers they quickly become waterlogged and drown. If they crash land in the sea they rarely get airborne again, because of their long unwieldy wings and the inadequate propulsion from their small, unwebbed feet.

Hunting for food

In contrast to their helplessness on the ground and on the sea, frigatebirds are champions in the air. They feed mainly by swooping to grab airborne flyingfish and other small fish jumping to escape predatory fish. They also use their long hooked beak to pluck small fish and other creatures from the surface of the sea. Over land they swoop to prey on turtle hatchings, the unprotected young of other seabirds, unprotected domestic chicks, and small rats. Frigates are the only seabirds in the Cook Islands that occasionally drink from freshwater ponds. This unusual behaviour is sometimes seen at the lake in ‘Ātiu, where a bird will fly low with its lower bill skimming the water.

Pirate, thief, and parasite

Although frigatebirds are mainly predators of live fish and other animals at the ocean surface, they are also well-known pirates, stealing the food caught by other seabirds. While frigates soar over the coast they are watching for other seabirds labouring ashore with a gullet full of food. Being much faster and more agile, one or more frigates can swoop down to harass the victim until it regurgitates its food, which a frigate will grab with its beak as it drops or from the sea before it sinks. The harassing involves flying closely above, to force the bird down towards the sea, and using its long beak to pull the victim's tail or wing. I watched a frigate force a Brown Booby to within a few metres of the ocean and then pull its tail up and forward causing it to crash land – in this case the booby did not regurgitate its cargo (if it had any). The usual victims are Red-footed Boobies (Toroa), Brown Boobies (Kena), Brown Noddies (Ngōio), Red-tailed Tropicbirds (Tavake), and some terns, but rarely White Terns (Kākāia), which carry only one or two small fish sideways in their bill. Feeding on other birds is being a parasite, and this thieving style of parasitism makes a frigate a kleptoparasite, a "thief parasite".

The spectacular soaring of frigates and the dramatic attacks on other birds reminded early sailors of the navy's Man-o'-War ships, in particular the Frigate, the medium-sized Man-o'-War. Thus the sailors called these birds Man-o'-War Birds and Frigate Birds.

Courtship and breeding

Frigatebirds nest on the ground, on shrubs, and on the crowns of trees. Courtship is spectacular with a male sitting on a nest site with its bright red throat-sac inflated, wings outspread and quivering, and emitting a curious piping call to entice a female flying overhead to land and inspect. If she approves, they build or improve the nest with twigs picked from beaches and elsewhere. The female lays one egg and it will be a year before she has a fully independent young. The egg takes two months to hatch, and the hatchling takes six months until it can fly – and for more than four months the fledgling returns to the nest site at night to be feed by its mother. This is the longest breeding cycle of any tropical seabird, and females can breed only every second year.

While frigatebirds are master pirates in the air, they are pathetically vulnerable in their nesting colonies. In the Cook Islands they maintain significant breeding colonies only on the unpeopled islands of Suwarrow and Takūtea. They cannot survive if regularly disturbed by people. When people approach a frigatebird colony many of the adults are frightened into the air, where their thieving and predatory instincts take over. They destroy undefended nests by stealing the nesting material, and they attack unprotected, small nestlings.

Cook Islands' colonies

The breeding colonies of the two Cook Islands' species of frigatebirds have been poorly researched. On Suwarrow three estimates since 1985 range from 1,000 to 8,500 nests for the Lesser Frigatebird, most nesting on the ground; and range from 100 to 250 for the Great Frigatebird, with most nesting on Pemphis shrubs (Pemphis acidula, Ngangie). BirdLife International has identified Suwarrow as one of the world's Important Bird Areas because it supports more than 9% of the world's Lesser Frigatebirds, and has more than 70,000 nests of the Sooty Tern.

Takūtea has the only colony of frigatebirds in the Southern Group - a small colony of Great Frigatebirds nesting on the flattened crowns of a small Pisonia forest (Pisonia grandis, Pukatea). In 1990 the colony was estimated to have 100 nests, with eggs having been laid between February and June. This small colony is particularly vulnerable to disturbance when visitors walk under the trees.

The Cook Islands has a special association with the Great Frigatebird because Doctor Anderson collected the first specimen for science when he visited the unpeopled atoll of Palmerston in April 1777 with Captain Cook. The scientist who named it in 1789 thought it was a pelican, because of the throat-sac, and named it Pelecanus minor, "Small Pelican". Later it was re-classified to Fregata minor with the English name Great Frigatebird. Concerning the birds of Palmerston in 1777, Captain Clerk wrote: "The immense Quantities of [seabirds], which consisted chiefly of Men of War and Tropic Birds, Boobies, Noddies and Egg Birds, are astonishing, the Trees and Bows in many places seem’d absolutely loaded with them". Today the colonies of frigatebirds, Egg Birds [Sooty Terns], and boobies are gone, while carefully regulated harvesting of tropicbirds has enabled them to survive. It is important to protect the few colonies of frigatebirds, Sooty Terns, and boobies that have survived on the unpeopled islands of Suwarrow and Takūtea.

The Cook Islands has a special association with the Great Frigatebird because Doctor Anderson collected the first specimen for science when he visited the unpeopled atoll of Palmerston in April 1777 with Captain Cook. The scientist who named it in 1789 thought it was a pelican, because of the throat-sac, and named it Pelecanus minor, "Small Pelican". Later it was re-classified to Fregata minor with the English name Great Frigatebird. Concerning the birds of Palmerston in 1777, Captain Clerk wrote: "The immense Quantities of [seabirds], which consisted chiefly of Men of War and Tropic Birds, Boobies, Noddies and Egg Birds, are astonishing, the Trees and Bows in many places seem’d absolutely loaded with them". Today the colonies of frigatebirds, Egg Birds [Sooty Terns], and boobies are gone, while carefully regulated harvesting of tropicbirds has enabled them to survive. It is important to protect the few colonies of frigatebirds, Sooty Terns, and boobies that have survived on the unpeopled islands of Suwarrow and Takūtea.

Traditional Names

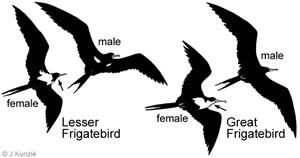

The Cook Islands has two species of frigatebirds: Great Frigatebirds (Fregata minor) and Lesser Frigatebirds (Fregata ariel). In the Southern Group the name Kōta‘a covers both species. In general appearance the males of the two species are very alike, entirely black or almost so, and they differ from the females of both species, which are black with white breasts. It is not surprising that the division into two types in the Northern Group is based on gender rather than on species. On Tongareva, Manihiki, and Rakahanga the males, with their red throat-pouches, are Kōtaha Tarakura while the females are Kōtaha Māri. On Pukapuka the females of both species are Kotawa Umalawa, and while Kolokolo Kura refers to any male, the males of the two species are distinguished as: Kotawa Koyi (Lesser) and Kotawa Uyi (Great). Recently developed species-specific names used in the Natural Heritage Project are: Kōta‘a Iti for the Lesser, and Kōta‘a Nui for the Great.

First published in the Cook Island News 21 May 2005.

Image Credits: Judith Kunzle (Species and gender differences), and Donna O'Daniel (Great Frigatebird courtship)

About Gerald McCormack

Gerald McCormack has worked for the Cook Islands Government since 1980. In 1990 he became the director and researcher for the Cook Islands Natural Heritage Project - a Trust since 1999.

He is the lead developer of the Biodiversity Database, which is based on information from local and overseas experts, fieldwork and library research. He is an accomplished photographer.

Gerald McCormack has worked for the Cook Islands Government since 1980. In 1990 he became the director and researcher for the Cook Islands Natural Heritage Project - a Trust since 1999.

He is the lead developer of the Biodiversity Database, which is based on information from local and overseas experts, fieldwork and library research. He is an accomplished photographer.

Citation Information

McCormack, Gerald (2005) Frigatebirds - Our Vulnerable Pirates. Cook Islands Natural Heritage Trust, Rarotonga. Online at http://cookislands.bishopmuseum.org. ![]()

Please refer to our use policy